Chapter 1

In mid-16th century England, there were rumors of the epic proportion that had spread throughout the kingdom and beyond. These rumors are what will be examined in this article.

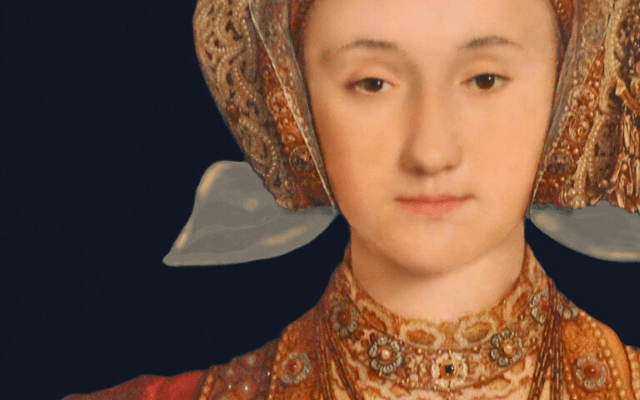

Rumor: Anne of Cleves had one, maybe two children by Henry VIII after they were separated from marriage.

At this time in England, Henry VIII’s fifth wife, Katherine Howard was being exposed for her past indiscretions along with her adulterous relationship with Thomas Culpeper.

King Henry was devastated by his queen’s actions. Katherine Howard was his fifth wife and he still had only one legitimate male heir and two illegitimate daughters. As his father’s son, Henry always had the line of succession in the back of his mind. It was his duty as a Tudor king to keep the dynasty going as long as she could, with sons.

To find out more about these rumors we looked through Royal State Papers & Letters, Proceedings and Ordinances and books to gather all the pertinent information to make an educated guess as to what was true and what was false. After all, the only person who could answer this question is long gone. Anne of Cleves.

If you have ever watched the TV series, “The Tudors” you’ll remember an episode that, if I remember correctly, was at Hampton Court where Henry and Anne of Cleves were playing cards together in candlelight. They were laughing and having a good time in each other’s company. Looks exchanged between the two led me, as a viewer, to believe that they may have slept together following the conclusion of their game. Was this scene based on the rumor we are uncovering today?

“And if, after the King’s death, she have no children surviving and would rather return to her own country” she was free to do so.

After the death of Henry VIII in 1547, Anne of Cleves remained in England until her death a decade later. Does this mean she stayed in England because she had a living child or children? If not, is it possible that Anne chose to stay in England because it was agreeable to her? We also know that after the death of the King there was not much left for Anne in Cleves. We also know that she enjoyed the company of her step-children: Edward, Mary & Elizabeth – maybe that is why she stayed.

In looking for the first evidence of any discussion of the matter I came across evidence from Alison Weir where she says:

On 22 October, Henry VIII, while at The More in Hertfordshire was astonished to learn there was a rumor circulating that he had impregnated Lady Anne of Cleves while he had visited her in Richmond in August. Henry was relieved to discover after investigation that Anne had been confined to bed for only an upset stomach. Someone had suggested and rumored that it was morning sickness.

The above statement from Alison Weir’s book is interesting, however, I was unable to find any evidence of it in the State Papers, which is listed as her source. Let’s keep that in mind while following this timeline. However, this is the first evidence that there is a likelihood that Henry had slept with Anne, at some point – otherwise why would he have been relieved?

As we know, the marriage between Henry VIII and Katherine Howard was short-lived. He loved her very much and it has been noted often how much affection he showed her in public.

In November/December 1541 , not long after the arrest of Katherine Howard, Anne of Cleves was noted to have fallen ill. Some at the time believed it was not an ailment at all but more a mental state. After Anne heard of the arrest of Katherine Howard she became ill. At the time that she fell ill her favorite lady (who would care for her person), Dorothea was in child-birth – so Elizabeth Bassett and Jane Ratsey were to attend Anne in her place.

While she lay in bed, Anne overheard Jane Ratsey say, “It’s God’s working in his own way to make Milady Anne queen again!” Anne, upset by what she heard made sure (in her weakened state) to firmly reprimand Jane for her inaccurate statement. Anne understood the consequences of saying such things. Unfortunately, the damage was already done. Others had overheard what Jane had said and were actively repeating it.

Not long after the event, both Jane Ratsey and Elizabeth Bassett were apprehended and questioned.

Attempting to cheer up her friend, Dorothea brought Anne her newborn son, William. It is believed that this is where the rumor of Anne having a fair son began. The image of Lady Anne with a child in her bed was enough to start the rumor. Words had spread that the child was Anne’s. This of course was untrue as the child was Dorothea’s. Let’s keep in mind that the previous statement came from a novel, but an interesting statement nonetheless. I apologize, I appreciate the ‘what-ifs’ of history.

It is perceived, that at the time, Anne went along with the story because she feared for her safety from the King. If Henry heard that she had his son he would spare her life if she were ever in a situation where it was needed.

Sir Thomas Wharton wrote to the Council on 4 December 1541, that Jane Ratsey was examined for her statement. He states that it was idle saying suggested by Bassett’s praising the Lady Anne and dispraising of Katherine Howard. She also said, under examination that she believed the King’s divorce from Anne was good. Jane was asked why she also said, “What a man is the King! How many wives will he have?? She said it upon the sudden tidings declared to her by Bassett when she felt sorry for Katherine Howard but did not know at the time what the charges were against her.

Around the same time, the Council wrote to Sir Anthony Browne and Sadler – written in the handwriting of Wriothesley:

We examined also, partially before dinner and partially after, a new matter, that the Lady Anne of Cleves should be delivered of a fair boy, and whose should it be but the Kings Majesty, and gotten when she was at Hampton Court; which is most abomynal slander, and for this time, and the case in ‘ure’, as we think, most necessary to be met with all. This matter was told to Taverner, of the Signet, more than a fortnight ago, both by his mother-in-law, Lambert’s wife, the goldsmith, and by Taverns own wife, who says she heard it from Lilgraves’ wife, and Lambert’s wife heard it also from old Lady Carew; Taverner kept it and they, with others, have made it a common matter of talk and never revealed it ’til Sunday night – at which time he told it to Doctor Cox, to be further declared, if he thought good; who immediately disclosed it to me, the Lord Privy Seal. We have committed Taverner to the custody of me, the Bishop of Winchester, and Lambert’s wife, who seems to have been a dunse in it, to M’ the Chauncelour of the Augmentacious.4

Only a day later we find out that Frances Lilgrave had indeed openly communicated slander of the Lady Anne and the King when she affirmed to have heard that the Lady Anne delivered a son by the King, and yet she could not, or would not name others that she had heard it from. She was sent to the Tower.5

That very day, Richard Taverner, one of the King’s Clerks of Signet was also apprehended for both concealing the slander he overheard and who also reporting it himself to others. He was also committed to the Tower.5

In the book, Memoirs of the Queens of Henry VIII, and his Mother Elizabeth of York by Agnes Strickland, it states that Anne’s lady, Dorothea/Dorothy was also thoroughly examined by the Council. Strickland also states that Lilgrave refused to name who she heard it from.

Richard Taverner was a Clerk of Signet. A Clerk of Signet was an English official who played an intermediate role in the passage of letters patent through the seals. He worked for the king and was responsible to him. The fact that he was involved in the scandal was shameful. Taverner is also known for translating the Bible in 1539 – it was called, Taverner’s Bible.

Sources:

The Six Wives of Henry VIII by Alison Weir, pg 436

My Lady of Cleves by Margaret Campbell Barnes

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/letters-papers-hen8/vol16/pp644-660

4 State Papers: King Henry VIII; Parts I and II, Volume I, pg 697-698

5 Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council of England: Henry VIII-5 December 1541

Memoirs of the Queens of Henry VIII, and his Mother Elizabeth of York by Agnes Strickland

—

Chapter 2

So here we are again, discussing how the matter needs to be thoroughly examined. The King is upset that none of Anne’s officers informed him of the matter. The matter that even the King was unsure was true.

Again on 7 December, the Council with the King wrote to the Council of London that the matter touching the Lady Anne of Cleves, the King thinks should be thoroughly examined, “and further ordered by your discretion as the nature and quality of the case requires; and to enquire diligently whether the said Lady Anne of Cleves hath, indeed, had any child or no, as it is bruited (reported);” The King has been informed that it is true; in which case the King is very upset with Anne’s officers for not relaying the news. Without doubt, your Lordships (Council) will thoroughly examine the information and find out the truth of the whole matter, and relay the results to the King.

Only two days later the wheels were in motion. The Council in London reported to The Council with the King:

We have also sent for the officers of the Lady Anne of Cleves and for Dorothy (Dorothea) Wingifeld, John Wingfield’s wife which is of her privy chamber; and have committed Taverner, and Lilgrave’s widow (Frances), who apparently yet the first author of the bruit, to the Tower. And we have also travailed to the best of our powers, with Jane Ratsey; and more than she hath already confessed we cannot get of her, albeit we have once committed her to the Lieutenant, as though she should have been committed to the Tower, and finally left her in the custody of me, the Lord Chancellor. The woman seems most sorrowful, as to have been moved upon none other occasion then is before written. Desiring you, also, to know His Majesty’s pleasure what shall be further done with her, accordingly. And thus we commit you to the keeping of Almighty God.

To summarize, Anne’s lady Dorothea was sent in for questioning after Taverner and Lilgrave had already been sent to the Tower, and Ratsey was being held for their involvement in the matter.

On the same day, the Council discussed the matter of the rumor about Anne of Cleves having a son by the King and being pregnant with another by him. The rumor about the son was that he was born at one of her country houses in the Summer of 1541. They suspected that both rumors were spread by Protestants. They discussed all day and decided they didn’t have time to delve much further into it as they had enough on their plate with the scandal of Henry’s current queen, Katherine Howard. The Council discussed the matter of Lady Anne with the King who requested a full enquiry into said matter.

I find that exchange most intriguing – we have to remember while going along on this timeline that the Katherine Howard investigation was going on at the same time. The Council had their hands full trying to get to the bottom of the Katherine Howard drama, and the idea of also having to investigate something that seemed like a rumor to them seemed like too much. However, the King insisted.

Imagine how Henry VIII felt at the time. One wife was being accused of adultery and then having to deal with the rumors of your ex-wife possibly having your child (and a son at that) and didn’t bother to tell you. That would be a lot for any person to digest.

Not long after the execution of Katherine’s lover, Thomas Culpeper, Henry felt the need to escape.

In the meanwhile Henry sought such distraction as he might at Oatlands and other country places, solaced by music and mummers, whilst Norfolk, in grief and apprehension, lurked on his own lands, and Gardiner kept a firm hand upon affairs. The discomfiture of the Howards, who had brought about the Catholic reaction, gave new hope to the Protestants that the wheel of fate was turning in their favour. Anne of Cleves, they began to whisper, had been confined of ‘a fair boy’; ‘and whose should it be but the King’s Majesty’s, begotten when she was at Hampton Court?’ This rumour, which the King, apparently, was inclined to believe, gave great offence and annoyance to him and his Council, as did the severely repressed but frequent statements that he intended to take back his repudiated wife. It was not irresponsible gossip alone that took this turn, for on the 12th December the ambassador from the Duke of Cleves brought letters to Cranmer at Lambeth from Chancellor Olsiliger, who had negotiated the marriage, commending to him the reconciliation of Henry with Anne. Cranmer, who understood perfectly well that with Gardiner as the King’s factotum such a thing was impossible, was frightened out of his wits by such a suggestion, andpromptly assured Henry that he had declined to discuss it without the Sovereign’s orders.4

The biggest question from the above quoted book is why does it state that Henry was inclined to believe the rumor? Had he and Anne slept together after their divorce/annulment? Was it a true statement to say that he believed the rumor? I often wonder why he called for an investigation if he had not previously slept with the Lady Cleves.

The fate of Jane Ratsey was decided after the results from her interrogation were released:

Fynally, thes being all the poyntes answerable in your said letters, saving onely touching Jane Ratsey; whom the Kinges Majeste, understonding sorowfulnes for her faulte, and gracyously wayeng her wordes to proced rather lightnes, then of anye malice is content that ye shall discharge and set at lybertee, with such good advyse and exhoracion to be given unto her, as by your wisedomes, shalbe thought convenyent.5

Jane Ratsey was released by the King and free to go after showing remorselessness for her actions. The same went for Taverner and Lilgrave- they were also released from the Tower not long after being placed there.

The King’s Council documented on 11 December 1541, that they had also sent letters to both Fr. William Goring, Anne’s Chamberlain, and Jasper Horsey, her steward, to report to the King’s Council for questioning.

After hearing about the arrests of a couple of Anne’s household, Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Spanish Ambassador, wrote to the Emperor to inform him of the events occurring at the English court:

Two honest citizens were three days ago confined to prison for having lately stated, after the publication of this queen’s misbehaviour, that the whole thing seemed to them a judgment of God, for, after all, Mme. de Cleves was really the King’s wife, and, although the rumour had been purposely spread that the King had had no connection whatever with her, yet the contrary might be asserted, since she was known to have gone away [from London] in the family way from the King, and had actually been confined this last summer, the rumour of which confinement, real or supposed, has widely circulated among the people. (fn. n13) London, 11 December 1541.

Two days after sending the letters the King’s Council had questioned both Goring and Horsey and they were both dismissed the same day after their questioning commenced.

Sources:

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/letters-papers-hen8/vol16/pp660-671

The Council with the King to the Council of London, Minute written by Sadler: 7 December 1541

The Six Wives of Henry VIII, Alison Weir, pg 473

4 The Wives of Henry the Eighth and the Parts They Played in History by Martin A.S. Hume, pg 387

5 A letter from The Council with the King to the Council in London, 10 December 1541

—

Chapter 3

Interestingly enough, Thomas Cranmer was approached by the ambassador to the Duke of Cleves on the 13th of December 1541. The ambassador was pushing for the King’s reconciliation with Lady Anne, and that the King should marry her again because of his trouble with the line of succession. Cranmer informed the ambassador that he could not answer without first speaking with the King.

The reason I find this interesting is because the King’s succession is mentioned. At this time the King already had a legitimate son, Edward. Had Anne indeed given birth to a son and this was the way for the Duke to have his nephew legitimized and placed in the line of succession, or was this just his way to gain himself a stronger alliance with England?

On 16 December 1541, the French Ambassador (Marrillac) joins in on sharing with King Francis I to inform him of the Ambassador Duke of Cleves intentions in England:

The Ambassador of Cleves told Marrillac that upon receiving letters from his master he was looking to speak with the King about the Lady Anne. But the King was still grieving (about the betrayal of Katherine Howard) and would not be available to him. Instead, the Ambassador of Cleves went before the Council and, after declaring his master’s thanks for the King’s liberality to his sister, pray them to find means to reconcile the marriage and restore her to the estate of queen. The Council answered on the King’s behalf that Anne should be graciously entertained and her estate rather increased than diminished, but the separation had been made for such just cause that he prayed the Duke never to make such a request. The Ambassador, realizing he upset the men, did not press the matter any further for fear of hurting matters for the Lady Anne.

…..One year later…..

On 26 January 1542, William Paget wrote from Paris that he wanted to let the King know he heard of “a certain declamation” made in French by a gentleman of the Court (as he was informed) about His Majesty and his Council, in Lady Anne of Cleves’ name and found the means to get a copy of it. “Where Your Majesty shall perceive that, with words only, and under the shadow of a humble and obedient oration, the author goes about to confute Your Majesties just proceeding touching the repudiation of the said Lady.” He goes on to say that he will find the author.

Is it possible that what Paget writes about pertains to Henry’s divorce of Anne of Cleves? It seems that a year and a half later is a long time to still be gossiping about it, so is it possible that this is a rumor in Paris about Anne’s pregnancy?

Only weeks after the execution of Katherine Howard, on 25 February 1542, the Imperial Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys wrote to Emperor Charles V that the Duke of Cleves is attempting to convince the King to remarry his sister.

…Four Years Later…

On 23 May 1546, John Dymock, commissary of the King was at the house of Walter Henricks in Cronenborch, in the state of Dordrecht (Netherlands). While there the bailiff of Dordrecht, with Doctor Nicholas and the bailiff asked him to host dinner. Shortly after the Procureur General and three other joined them. The Procureur asked Dymock not to take ill what should be said to him in confidence, and first Van Henluyden asked if it were true that the King had taken again Lady Anne of Cleves and had two children by her. Dymock answered that they in England knew no more than he had heard here – it was a matter between God and the King.

John Dymock writes on the matter again on 26 May 1546, when he pens a letter to Stephen Vaughn, who was Henry’s royal agent in the Netherlands. This time he explains the conversation further. When asked about the King taking again Lady Anne of Cleves and having two children with her, Dymock replied with “Somewhat abashed I answered that I heard this of the Emperor’s subjects, but knew only that she “goes and comes to Court at her pleasure” and has an honest dowry to live upon; the King would not have put her away without cause and do in his realm what he and his Council reckoned to be “for his commonwealth..”

From my findings, May 1546, was the last time the matter was documented.

When I began this research I thought Anne of Cleves might have given birth to at least one of Henry’s children. After concluding my research and presenting the evidence it seems more clear to me now that she most likely did not.

At the beginning, I really didn’t believe Henry ever slept with Anne. I mean, he couldn’t consummate the marriage, so why would he sleep with her later? However, after reading that Henry may have believed the rumors about Anne carrying his child, I tend to believe that they did at some point (after he had married Katherine Howard) sleep together. To me, this would be the only explanation for Henry pushing for a thorough investigation when his life was already in shambles with Katherine Howard cheating on him. It’s as if the prospect of a son would bring him out of the darkness.

It is most likely that the rumors we’ve covered here started by some of the ladies of her household, or Protestants trying to stir up problems for Henry. It is also possible that Anne went along with the rumors to protect herself from the king. She feared what happened to his other queens could happen to her after she witnessed the downfall of Katherine Howard. If rumor had spread that she had his son then he would be less likely to harm her – or so one would hope.

I’d be interested in what you think…please share!

—

Sources:

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/letters-papers-hen8/vol16/pp671-681

State Papers, King Henry the Eighth; Part V, page 652

Letters and Papers, Foreign Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII, pg 457

The End

Get Notified

I’ve read a post, can’t remember where now, about a man who professes to be descended from Anne of Cleves and Henry VIII. Can’t remember his name offhand. Does anyone know about this? The man professes Anne had a son and daughter for Henry.

According to Lucy Worsley’s* documentary on Henry’s wives, Anne of Cleves was called the “Sister of the King” after their divorce, he made her one of the richest women in England for smartly not defying his wish to divorce and Henry was uninterested in remarrying her after the Katherine Howard incident.

Ms. Worsley also tells a story of how the King came to meet Anne when she arrived in England (speaking little English) and masqueraded as Robin Hood, a trick he’d played before but Anne not knowing who this stranger was stepped back when he made an overture to embrace her. As depicted in the reenactment, she stepped back twice each time he reached for her until someone said, “der Koenig” (the king) and then she and everyone else present bowed or curtsied. Still, Henry was deeply humiliated and blamed Hans Holbein for making her look more attractive in her portrait than she was (clearly sour grapes.) Henceforward she was always known as the homely queen but there were a couple descriptions from other people quoted in the documentary calling her quite pretty.

It doesn’t seem to have occurred to the blogger that the King might have been concerned to track down the source of this false rumor, rather than believing that Anne had actually given birth.

Another source that Lucy Worsley quoted said that the King would just say to Anne “Good Night dearest”, kiss her forehead and roll over in bed and the hearer of this story from Anne was so incredulous that she said something to the effect that Anne would never get a baby that way.

At any rate, Anne has long been my favorite for keeping her wits and her head.

* (head curator of all museums in London)

First off I would like to say fantastic blog! I had a quick

question in which I’d like to ask if you do not mind. I was curious to find out how you center yourself and clear your head before writing.

I have had a hard time clearing my thoughts in getting my thoughts out there.

I truly do take pleasure in writing however it just seems like the first 10

to 15 minutes tend to be wasted simply just trying to figure out

how to begin. Any suggestions or hints? Many thanks!

If there is an apparent evidence Anne of Cleves had children, so whose were they if not King Henry’s? It is very common that ex-spouses go back together. Anne of Cleves would suddenly be attractive after the fiasco with Katherine Howard, a mere child bride. King Henry appeared to be very careless about keeping his seed outside of the women’s body. He fathered children with mistresses, why not Anne of Cleves too? It is just logical and quite possible.

Lastly: Would an entire line of Chalfant descendants carry the story of the Kings daughters 450 years downline to family members of Nebraska near my father’s homstead as a MISTAKEN notion handed down through their family generation after generation? Behavior of persons who believe in the story of Jesus of Nazareth are considered either NUTS or true Christians for how they acted upon their belief set the entire Western World on it’s course of History. In exactly the same way you must decide if your distance from this event has colored your view of the events or do you believe the actions of persons who based their entire lives upon the judgement and testimony of the Chalfant family descendants and the projenty who actually Look like King Henry Tudor and his family in 12 different cases….only possible by genetic messageing of 4 lines merged into one. DCR

Further: The Queen’s twin girls were thought to be raised Catholic. Anne is descended from the sister of the Holy Roman Emperor of Spain hense the DNA is J1a from Central Spain as passed onto my mother and her sisters. Besides baring a doppleganger likenss to Elizabeth Tudor the women who recently lived in the Chalfant line look nearly exactly like Elizabeth Tudor. We Children are mixed Tudor and Sutton Dudley and thus we do not share the exactitude of facial imaging for the X chromosome passed down from Anne. However: My mother is a doppleganger of Anne’s sister AMALIA….Thus both The German Princess connection to Spain is represented in her more direct and exclusive Tudor line. See Breeding BACK: a technique to ressurect the elements of features in lines thought to be extinct.

DCR 1948

William Chalfant 1541 is listed by GENI as my 13th great grandfather….William Would be the fostered childe of Margaret Artbroke and William Chalfant Stewards at Widsor Castle for generations. They are 3rd or 4th cousins to Elizabeth Blount mother of Henry Fitzroy and Elizabeth Tailboys. Both are listed by Geni as my 4th cousins. The reason my father chose my mother as his bride was her descent from William Chalfant 1541 and his descent from the Children of Ethelralda Maulte. We 7 Nebraska children of Samuel Gordon Rice 1887 and Mildred Cookston 1910 bare unusual likeness to the this double line descent from the Tudors. Dopple Gangers include Henry II of France Louis Valois VIIII King of France, 2 of us share the face of Henry VIII and a sister of Elizabeth Tailboys our 4th cousin. D. Charles Rice 1948 of the Nebraska Rices

Anne of Cleves was rumoured to be with child and there was a major concern from Catherine Howard that Henry would leave her and go back to Anne. This was due to his regular visits to Anne at Hever and his depression and removal of himself from Catherine for a month in 1541. However, he soon put an end to the rumours and Anne was not pregnant. She was treated well by Henry and given several homes and two palaces as well as a good income. She supped with Henry and Catherine at New Year 1541 and sent four horses to the new young Queen. Anne greeted her former Maid on her knees and showed her due honour. She danced with them both later on and was their guest. Anne decided to remain in England because she was happy and she had close ties to all of Henry’s children. Although her life was made uneasy under Edward, she was good friends with Mary. A short period of friction came but was resolved and no, Anne of Cleves was not a Lutheran. Along with her mother and sisters she was raised a Catholic and remained one. She is the only one of the Six Queens buried in Westminster Abbey.

I have read Anne considered herself Henry’s true wife for the rest of her life. Why if the marriage was never consummated. Isn’t it curious she appears to have had no other romances or men in her life after the divorce despite being one of the wealthiest women in England? Not if you believed yourself already married. Imagine her positon, a stranger in a foreign country married to a tyrant with a habit of killing his wives. Once she realized the way the wind was blowing with Katherine Howard, she might have decided I will say whatever he wants me to say to stay alive. Another curious point is that he forbade her to leave England after the divorce and would not allow her return to Cleves until after he died. Was it because she might say the marriage was consummated and cause a diplomatic incident? Finally, if she did become pregnant there are sound reasons for her to hide it. Yes, Henry would have exalted her to the heavens if she had a son. But what if the child was a girl. She would be tied to a man who was very mercurial and made it plain he did not love her. I would not want to be in her positon. Its all speculation but its worth a novel or two.

It could be that, as a Roman Catholic, Anne of Cleves may have seen herself as married in the eyes of the “True Church”, since she and Henry were married by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, who had received his pallium from Pope Clement VII. That meant he got his Archepiscopal blessing from the Pope, who got his Apostolic power to bind and loose from the Apostle Peter, who got it from Jesus Christ.

Henry VIII was a widower. Anne of Cleves was a single woman, She may have become convinced that her betrothal to the son of the Duke of Lorraine was automatically null and void because it was made when she was 12 twelve and the boy 10 years old and had not been ratified when they were at the age of consent.

So, Anne, after the annulment on the basis that she was pre-contracted to the Duke of Lorraine, may have been told by someone that, since that precontract had been made by children and had not been ratified when at the age of consent, that precontract was annulled. She consented to marry Henry VIII and Henry had consented to marry her. Like it or not, they were married in public, in the Church officiated by a priest who was ordained in his office by the papal descendant of the Apostle St. Peter and so she and Henry were truly married in the sight of God

Perhaps by her Catholic mother, or the Princess Mary, or Elizabeth Basset {if her brother was the Arthur Basset who married Sir Thomas More’s granddaughter Mary Roper. A member of the More circle may have put it into Elizabeth’s head] thought that way.

It’s just an idle thought. A speculation. Adding to my speculation is “What if the Princess Mary, or Bishop Gardiner of Winchester or Elizabeth Basset through her sister Anne [if Anne Basset and Arthur Basset were related to her. Anne was supposedly very good friends with King Henry, perhaps a mistress] had heard rumours that the King was enamoured with Katherine Parr. Katherine’s husband Lord Latimer was dying. Thomas Seymour was also sniffing around the to-be-widowed lady, and the lady was attracting gossip. The Seymours were “pro-religious-reform” or even “Protestant”. Katherine Parr was either rumoured to be “pro-religious-reform” like Archbishop Cranmer or to have discreet Protestant friends like Katherine Willoughby, Lady Suffolk. A lot of rumours could be buzzing about since Queen Katherine Howard was arrested and degraded.

Maybe the Lady / Princess Mary or the other Catholic leaners might have hoped that they could retrieve the Catholic situation by encouraging the King to take Anne back as his wife, since she was still his wife. The theologian and churchman in Henry might accept the point.

Of course Henry wanted nothing to do with Anne as his already wife. He could not go back on what he had done without his courtiers and the other kings snickering at him. Anne of Cleves was repugnant to him. That’s the real reason for that annulment and for Cromwell’s execution. It wasn’t said; but it was known. He wanted Katherine Parr, and he was going to marry her the moment after Lord Latimer was dead and Thomas Seymour was sent on a long embassy.

Anyway, I’d like to toss it into the mix with other “what if’s”, “guesses” “secrets” and things uncovered by new scholarship and by the popularity of the Tudors, and see if it floats or sinks.

Ive had a thought maybe Henry didnt want to shell out money to Anne of Cleves maybe he was hoping the charges she was pregnant were true so he could chop her head off which he seems to like doing to people who annoyed him and she did upset him previously im not sure if it would have affected the succession if she had a son with someone else

maybe just very embarrassing for him

Anne of Cleve never bore Henry VIII a child. The whole reason their marriage was dissolved was because Henry couldn’t consummate the marriage. Henry couldn’t stomach to intimately touch Anne, who he believed was never a virgin. Anne stayed in England as a condition of her position at court. Being the king’s sister, Anne had to cut ties with her brother and all correspondence inspected. Anne might have been afraid what her brother would do to her if she ever returned.

I think, Henry VIII never slept with Anne. Their first encounter went terribly wrong and he decided that Anne was physically unattractive. He said even some quite mean things about her and the marriage was not consummated. The arrangement of the marriage was even one of the aspects that brought Thomas Cromwell out of favour and led in parts to his downfall. If Henry VIII’s wanted to sleep with a woman, he could pick any from his court, so I do not think that he was desperate enough to turn to Anne. As to why she stayed in England, I also think it was much more comfortable for her to stay. She was her own mistress and she had a financial income from the royal household. That made her quite an independent woman as she could do whatever she liked and was free to move. A rare thing at that time. Why go back to Cleves and loose that freedom. She was also surrounded by her ladies and friends, was close to the royal children. To me it sounds quite a comfortable life for a woman in Tudor times.

Hi From all that I know about Henry VIII I find it really hard to believe that he slept with Anne. He didn’t like her and I’m sure he had no sexual interest in her at all. So no children

I apologize for this coming rather late, I hope it finds the author of this most informative essay.

From my research, I do not believe Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves consummated their marriage, nor do I believe they shared intimacies of a sexual nature post divorce. For all his faults, Henry remained devout and to have had relations with proclaimed “sister” would have been incredible, even to Henry. This and the legal argument sustaining the initial divorce would have precluded any potential reconciliation.

The inference you derive from Henry’s concerns about Anne’s having his child are legitimate, but can be explained easily without supposing Henry’s thinking the child was his. Rumors of Anne’s pregnancy and subsequent childbirth, even though Henry knew the child not to be his own would be a huge concern. Had Anne birthed the child of another man and succeeding rumors gained sufficient traction it would have called into question the line of succession.

No where in the citations does it indicate that Henry believed the alleged child was his, only that he was concerned. And I posit such concern would have been entirely well placed.

Let us also consider this contextually; Henry’s current wife, Katherine, was accused of sleeping with Thomas Culpepper — serious enough — but more so had she become pregnant, for how would legitimacy of the child have been established. And therein lies the real crime in her adultery. With this in mind, I think we can better understand Henry’s pushing for a thorough investigation into the alleged pregnancy of Anne of Cleves.

Fantastic comment – love the insight! Thank you. 🙂

Returning to Cleves may not have been a simple option for Anne. By returning, who knows who she might have been married off to next? In her time noble daughter’s lives & futures were not their own & they were casually bought & sold to the highest bidders to extend estates and grant power to the men in their families. They were seen a commodity and valuable asset.

By remaining in England Anne had title, status and wealth and a large estate that was very rare for women at the time. She also enjoyed a place at court and the King’s friendship. It seems to me that she made her choice (if it was truly her choice to make and not made for her) to go with what was a more certain and safe future. She most likely would have felt very fortunate to have any say in the matter at all.

Anne had no need to marry again as she had her own money so she could live a very comfortable life without dependence on a man or his family. (Sounds like a reasonable choice to me.)

With regard to the suggestion that Anne may have had a child by Henry, I find it odd that there seems no real mention of anyone asking Anne directly. This suggests that it was viewed as harmful gossip rather than potential fact. Why would the King not simply have sent someone to her house, search for this child and question her? Sounds more like he knew the truth.

I have read several books with Anne of Clever, and have gathered that her brother treated her horribly, and with zero respect afforded a sister by blood. Perhaps that fact had alot to do with her living out her life in England.

*Cleves

There is no evidence that her brother treated her with anything but respect and no proper history of her states that. You have been reading fiction. She was treated as a German Princess, a very sheltered life but one which was respectable and to protect her. To say she was treated horribly is to misunderstand the culture in which she was raised. However, she had far more freedom in England and would have felt embarrassed as a rejected bride. William might have felt obliged to go to war to defend her honour, but he had political messes of his own to fight.

William of Cleves was apparently horrible to his first wife, the Queen (or Heiress presumptive) of Navarre. It’s said that she was little more that a child and she had to be dragged to the altar. It’s said – rumour always seems to creep up – that the marriage was annulled because officially they didn’t consummate it but “really” because he brutalized her and she got word of it to her family. No evidence to support it.

Robert Hutchinson, in his book “The Last Days of Henry VIII” (p. 33) said “In return for remaining in England as ‘the King’s good sister”, where she would be firmly under Henry’s surveillance and control, Anne was to receive a generous annual pension for life … ” lands and manors and precedence ahead of all other ladies in England except for the current queen and Henry’s daughters.

In other words, Hutchinson said that King Henry did not want Anne to leave England. He wanted to control her behaviour and what she said. He was paranoid that Anne would tell nasty stories to her brother the Duke or to her sister, the wife of the Leader of the Protestant League in the German kingdoms. Maybe the Emperor’s agents would overhear something juicy is she was free to tell it. So his people dictated to her what she wrote to his brother and sister, or censored what she did write, and what she said to the Clevian ambassador, or they read her mail.

Anne might have – probably did – wanted to stay in England. In page 35 of Hutchinson’s book: “France’s new ambassador in London, Charles de Marillac, reported disapprovingly, ‘As for her who is now called Madame de Cleves, far from pretending to be married, she is as joyous as ever and wears new dresses every day.’ … Anne of Cleves began to enjoy drinking wine, casting aside her previous abstinence. She had metamorphosed into a rich, merry widow in all but name or title.” The Spanish Ambassador Chapuys hinted strongly, according to Hutchinson, [p. 52-53] that “if Henry cast Katherine aside ‘on account of her having had connexion with a man before her marriage to him, he would have been justified in doing the same with Madam de Cleves, for if the rumour current in the Low Countries was true, there were plenty of causes for a separation considering the queen’s [Anne of Cleves’] age [and] her being fond of wine, as they [the English] might have had occasion to observe, it was natural enough to suppose she had failed in the same manner.”

In other words, Anne was a mature woman, and she got drunk, so she probably had sex with a man prior to her own marriage to Henry. Henry had said himself that he had felt her lax breast and belly on their wedding night and concluded that Anne “was no maid”.

Henry might have worried that Anne was trying to get him to marry her again by having sex with other men, and then claim that she had birthed his baby boy. He had not believed Anne was a virgin on their wedding night, so he’d easily think nothing chaste of her after his “rose without a thorn” Katherine had deceived him with Culpepper. He’d believe he could not trust any woman not to cheat him with another man in their bed. [I suspect that Henry really did convince himself that Anne Boleyn had cheated on him too, just because Anne could have cheated on him. He had cheated on his previous wives. He even regretted marrying Jane Seymour when he saw two new women at court. He may have thought Katherine Parr was the safe exception to other women, because she wrote prayers.]

Why would she return to Cleves and be under the thumb of her brother? She had it made in England. Estates of her own and plenty of money in a time when women were subject to men and not many were in control of their futures. AND, from all that I have read, she and Henry were now great friends. What more could she want????

It would have been humiliating for Anne to return to Cleves as the “rejected wife”. I think she found life in England rather pleasant, and especially so if all she had to do was play cards once in a while with that grotesque, ill tempered ex-husband of hers!

Henry Might have slept with Anne, He may not have… I don’t think Anne of Cleves had any children with Henry. I believe that she stayed in England because she wanted to. Henry gave her a home, Ladies to wait on her.No.. I think she wanted to make England her home.

I think Henry wd have received organised a second son (and children) if Anne had had children with him. He was always on the look out for sons so I doubt he had any with Anne.

Re sex with Henry, it’s possible but who knows……

Interesting article.

The came out wrong!! It should say Henry wd have welcomed and recognised….

I don’t know very why Anne of Cleves remained in

England. She had to figure it out, her husband was

A womanizer. He remarried Shorty after the annulment of their marriage. If I had been her, I

Wouldn’t have stayed in a country where I was going to be treated as a sister. Maybe Anne would

Have had to be subject to her brother if she had

Returned home to Cleves.

Anne had no family in England. She was at the b

good graces of Henry VIII and his family.

Why didn’t she return to Cleves for a visit if she was

Home Sick. She must have figured Henry VIII out.

He lied to her. Shortly after the annulment he married a child bride, Catherine Howard??? If he had done me, that way, I would have been glad to

Leave England, but I’m not a woman.

Anne of Cleves stayed in England for a number of reasons, I believe. I believe that maybe, she did not like Cleves. That she was glad to be away from Cleves. Apparently her mother and brother were very strict and in England as her own mistress, she had freedom, like very few women at that time had. She only had to be wed a short time and then she was free with large properties, Richmond and Hever Castle to call her own and the favour of King Henry the Eight and she got on with Mary the First and Edward the Sixth and Elizabeth. She loved them and they loved her. She was welcomed at Court when she came to Court and she was allowed to remain on her estates if she wished. She could do as she pleased. If she wished to come to Court, she came. If she wished to remain on her estates, there she remained. It must have been nice to be able to do what she wished, when she wished. It would not have been like that in Cleves. No, she had no reason to go back to Cleves.

Henry VIII might not have allowed that, and so made the tempting deal of giving her a generous allowance, making her a rich woman and placing her in the spot above every woman but his current wife and daughters.

Robert Hutchinson, in his “The Last Days of Henry VIII” want Anne to remain in England in order to control her movements and what she wrote to her brother the Duke of Cleves and to her sister Sybilla, wife of the head of the German Protestant League. They were the closest he had to allies, should the Pope, the Emperor and the King of France wish to start a Holy War against him. [He could have ventured to ask the Ottoman Sultan for help; but that might be letting the wolf into the house. The people would not like to be eaten.]

Anne might not have wanted to cross the Channel again.

She couldn’t return to Cleves. The political situation made that impossible and within two years Kleves was involved in a territory war over Ghelders. Within a few years the United Duchies she knew as her homeland no longer existed as an independent entity. The Emperor Charles V took over control, her brother remained but it was under the Emperor. It wasn’t safe for her to return and why not remain? She was treated well, the people loved her, she had more freedom, she had independent wealth and status, she was at Court as a guest of honour often, she had two comfortable palaces, several homes, she was in touch with the King’s children, visited by Henry as his sister and friend, had many other friends, learned the language, to play and dance, gamble and she entertained. She was very wealthy and was buried with full honours in Westminster Abbey. Anna did far better remaining in England, rather than face humiliation at home.

Why would Anne of Cleves remain in England? Well, perhaps the question should be: why would she wish to return to Cleves? By staying in England she was to some extent mistress in her own household. Returning to Cleves would mean a much lower state, and the question what politics would mean to her. Being sent to yet another court? Another husband?

And had she given birth to a son, Henry’s son, that would have been the reason why she was sent to England. Wouldn’t have Henry just loved that??

The Tudors mini series was so rife with inaccuracies that I couldn’t watch much of it.

Anne of Cleves legal counsel had done a fabulous job of making sure the marriage contract would benefit her. Henry had little choice but to treat her well, and she, as the king’s “sister” had great freedom and wealth at her disposal. Her stepchildren were another great incentive to stay in England.

Me too!! I got half way through episode 1 and then have u on it. Total rubbish. Even the costumes were inaccurate, let alone the characters and storyline.

The TV mini-series https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0066714/

gave another more credible version of what happened between Anne of Cleves and Henry. And I agree, the Showtime series is just so unwatchable beginning with what has been descibed as the “anachronistically svelte” king Henry!